What is your backstory?

My name is Ward Long. I grew up in Los Angeles, went to school in North Carolina, and worked lots of weird jobs. After shooting on my own for a long time, I studied photography with some of my heroes at the Hartford Art School. Now I’m grateful to be part of a vibrant and dedicated community of photographers in and around Oakland, California. My debut photobook Summer Sublet came out earlier this year with Deadbeat Club.

What camera/editing setup do you use?

Right now I’m shooting Portra 400 metered at 200 on a Fuji G670iii. It’s a medium format rangefinder with a fixed normal lens and no meter. I scan the film at home and make small prints that I pin to the wall, tape into notebooks, and shuffle on the table like tarot cards.

When it comes time to make files for a book or exhibition prints, I drum scan the film. It’s an arcane, pain-staking process that took me a long time to learn, but the results are really worth all of the effort. All of that said, I end up switching cameras every project or so.

How do you achieve the look of your photographs and could you take us through the process?

I’ve worked with different approaches for different projects, but I don’t tend to think in terms of aesthetics or looks. I’m sure I have a style, but I try to keep that out of mind while I’m shooting. I do everything I can to stay in the moment. I watch the light and keep an open heart. I shoot with the sunshine, I move in close, and I hold the camera lightly. I try to be aware of my body moving through space, and watch for gestures, patterns, and play. I write every morning. After long years of anxiety, I learned how to mediate. Those things help so much.

In terms of post-production, I've made enough prints to know there’s a big difference between how the camera records and how the mind sees. Looking at a printed photograph is an open-ended experience that will be different for each person. Given that, I try to pack as much care and thought in there as I can. I want depth, I want detail, I want you to feel the air.

Could you tell us the backstory of some of your photographs?

I’ll focus on the backstory for the pictures from my new book Summer Sublet.

When I first moved to Oakland, I rented a small house by the water and the train tracks. There were tool sheds and rusting trucks in the yard. It was perfect for a while, but then the energy-healer-carpenter who owned the place kicked me out and turned it into a vacation rental.

When I lost my lease, Ara said there might be a room on Montgomery Street, and so I moved in with Alice, Hannah, Sarah, Bianca, and Kate. The house was by the art school and the women’s college, and it stacked full of mismatched, unclaimed belongings from several generations of roommates. At first I hid in my room and tried not to be noticed. I was so conspicuously male, and so out of proportion. I never had sisters.

They cooked together, mixed teas and tinctures, dyed fabrics in the backyard, designed costumes for children’s plays, wrote songs and poems, gave each other late-night tattoos, smithed jewelry, and stitched leather. They read tarot, talked aura, charted horoscopes, and parked their dirt bikes in the basement. The everyday physical and emotional closeness completely flooded me. I remember the first night we all said, “I love you,” before bed.

It all started to blur and bleed together. The paintings on the wall became our own poses, the drawings on your body drip back into the books on the shelf. I couldn’t believe the caring touches, the open hearts, the blushes of affection, the care and the clutter. I never wanted to move out.

You once made a book every week—what is the story behind that and the books?

When I was in grad school, I wanted to make the perfect book, something in the great American photographic tradition, something that cranky old Walker Evans would find worthy. It's good to be ambitious, but those impossibly heavy expectations weren’t helpful. Trying to make a flawless photobook was getting in the way of actually making the pictures—experimenting, reaching outside of my comfort zone, daring to fail. The perfect is the enemy of the good, y’know?

Jörg Colberg was my advisor at the time, and he picked up on my confusion. He came up with a devious but extremely helpful assignment—he challenged me to make a book every month for a year. I would give him the title on Day 1, shoot until Day 29, and then have all of Day 30 to edit and layout everything. It was the best assignment I ever got.

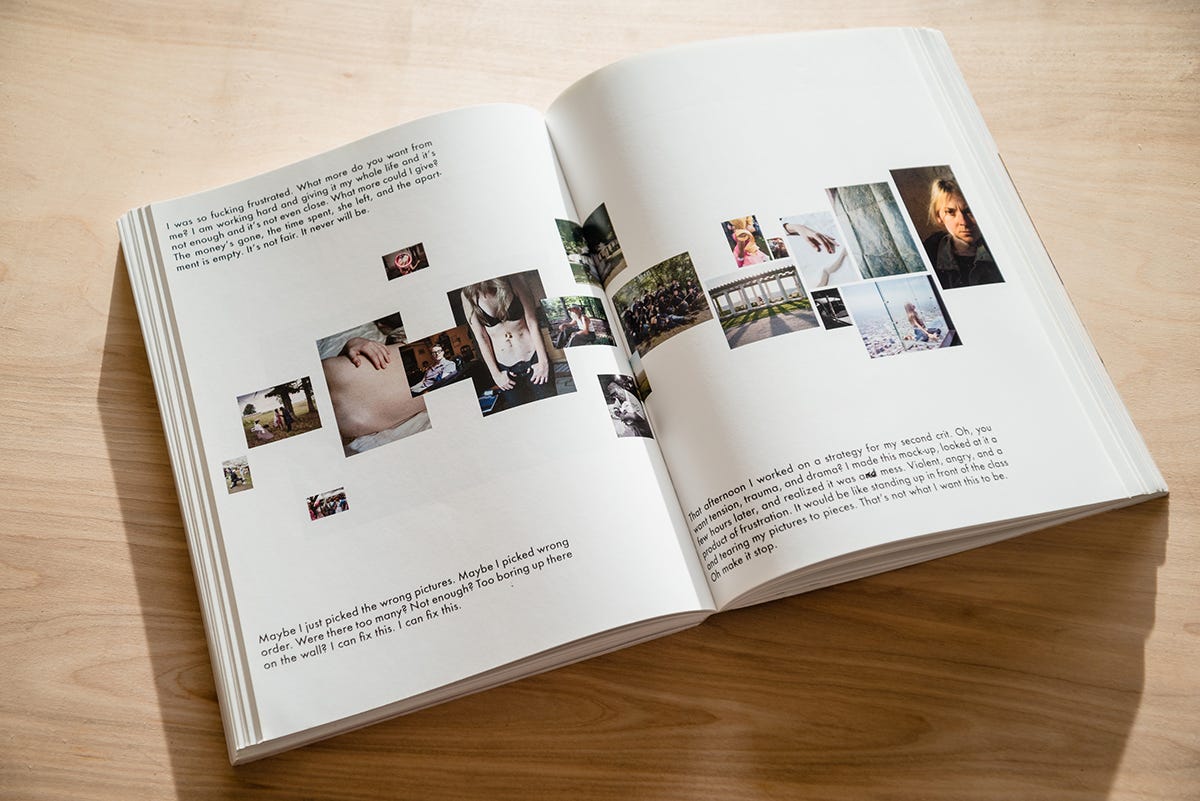

In the first few months, I made a few of my usual lyrical heartbreak books, but I was out of ideas by April. In the months ahead I cut up my pictures and collaged them, photographed myself at a cosplay festival, played with time and sequence, mixed text and image, wrote poems and made a book with every single reference jpg on my desktop. I got to know myself as an editor, learned to take myself less seriously, and started to see the gap between what my work was actually saying and what I just wished it said.

In the end I printed all twelve books as a single fat volume and made an edition of 2, one for me and one for Jörg.

What advice do you have for aspiring photographers?

Don’t quit.

Take a lot of pictures and spend time looking at them. Create a dedicated physical space to make art. Failure and rejection are part of the process; find a way to make your peace with both. Learn every part of the craft.

Read and see everything you can. Look carefully and practice noticing. Listen closely. Study the canon critically, and think about which voices have been left out. Search them out. Get a library card.

Get to know your own creative habits and project cycles. Work to make your practice sustainable. Learn how to help yourself.

Build community. Reach out to artists that you admire. Show pictures to other people, and figure out what kind of feedback is helpful for you and your work.

Find memoirs about a life in the arts by novelists and poets—they’ve been at it longer than us, and they’ve figured out how to keep going.

Make room for idle hours. Don’t let your day job take all day.