I am thrilled to present a special mini-interview with Caleb Stein about his ongoing new project, Men Fighting & The Spaces They Fight In.

Happy reading!

What is the backstory of Men Fighting & The Spaces They Fight In and could you tell us the backstory of some of the photographs?

While photographing at an Edenic watering hole in upstate New York for my long term series ‘Down by the Hudson’, I noticed that many men wrestle with their friends as soon as they get into the water. I am fascinated by how this sort of playful wrestling is a through-line in how men engage with their friends in this space. It’s how they relate to each other. It feels affectionate, platonic, playful, and vulnerable.

One photograph from ‘Down by the Hudson’ in particular has stayed with me. It’s a photograph of Bode and Owen wrestling in the water, their bodies pushed up against each - you can really feel the tension of one body extending its force into the other body and you can feel how those bodies interact with the creek, how the water moves around them. I exhibited that work at ROSEGALLERY in LA last year in a solo exhibition of prints from 'Down by the Hudson’. In a quiet moment during the installation, I was walking through the exhibition with Rose Shoshana and she told me that the photograph of Bode and Owen was going to stay in my head, that I was going to be working through the ideas in it for some time. And Rose was right - I have continued to look at men with tenderness as a way of complicating societal conceptions of masculinity, particularly heterosexual masculinity. I’ve been looking into how to make a picture that furthers this exploration of the complex ways in which men relate to each other and express themselves, and I’ve been asking myself how I can build up a sense of poetry and tension in that exploration, and, how to convey all of these questions with work that is sensual and strong at the same time.

It became a bit of a puzzle in my head: When a photograph looks soft - because of its forms, because of its light and its tonality, but it shows men that present themselves as tough (although there is tenderness suggested beneath that), then perhaps that’s a powerful way of questioning what it means to be a man today, to inhabit those contradictions between toughness and tenderness.

When I returned to New York after the exhibition in LA I decided I needed to develop a new body of work about men fighting. I contacted several professional fighters - fighters specializing in a range of disciplines including boxing, wrestling, mixed martial arts and jiu jitsu. Some of those fighters invited me to photograph their practices and their fights. I was interested in how these men have the ability to kill each other - many of them are internationally ranked fighters who compete all over the world - but the moment a fight is done they give each other a hug. There’s a sense of fraternity that surprised and inspired me - these men are comfortable with that sort of affection and they see fighting as an art form, as a dance of sorts, as a discipline, not as a means to violence, although their techniques can be deadly.

I’ve also been thinking through what it means to photograph fighting. There’s often a surprising stillness in these fights. When someone is about to be hit, or when someone is in a head lock, there’s an acceptance that comes over the man on the receiving end of that. There’s a humility to it and I hadn’t expected to see it in these spaces.

I’m interested in what it means to photograph fighting, especially since it’s something that’s been depicted since the beginning of humankind, and in some ways I’m interested in questioning that tradition of studying and celebrating the male body and its forms, but as a way of thinking through what it means to be a man today and what sort of space exists for men to be tender and strong simultaneously. ‘Men Fighting and the Spaces They Fight In’ is not a study of beauty for the sake of beauty. I’m not interested in simply engaging a tradition that extends back well before Greco-Roman sculpture for the sake of aligning with a certain type of style. I’m not interested in style for its own sake, that bores me. Each body of work I make begins with a feeling or a question or a concept and then I find the forms and the visual strategies that help me to dig deeper into myself and into the world. I’m very inspired by what Goethe said: “the world is richer than I am”, and so I’m interested in taking things as they come, in making work that comes from my heart and that flows naturally out of the experiences and questions I have in my own life.

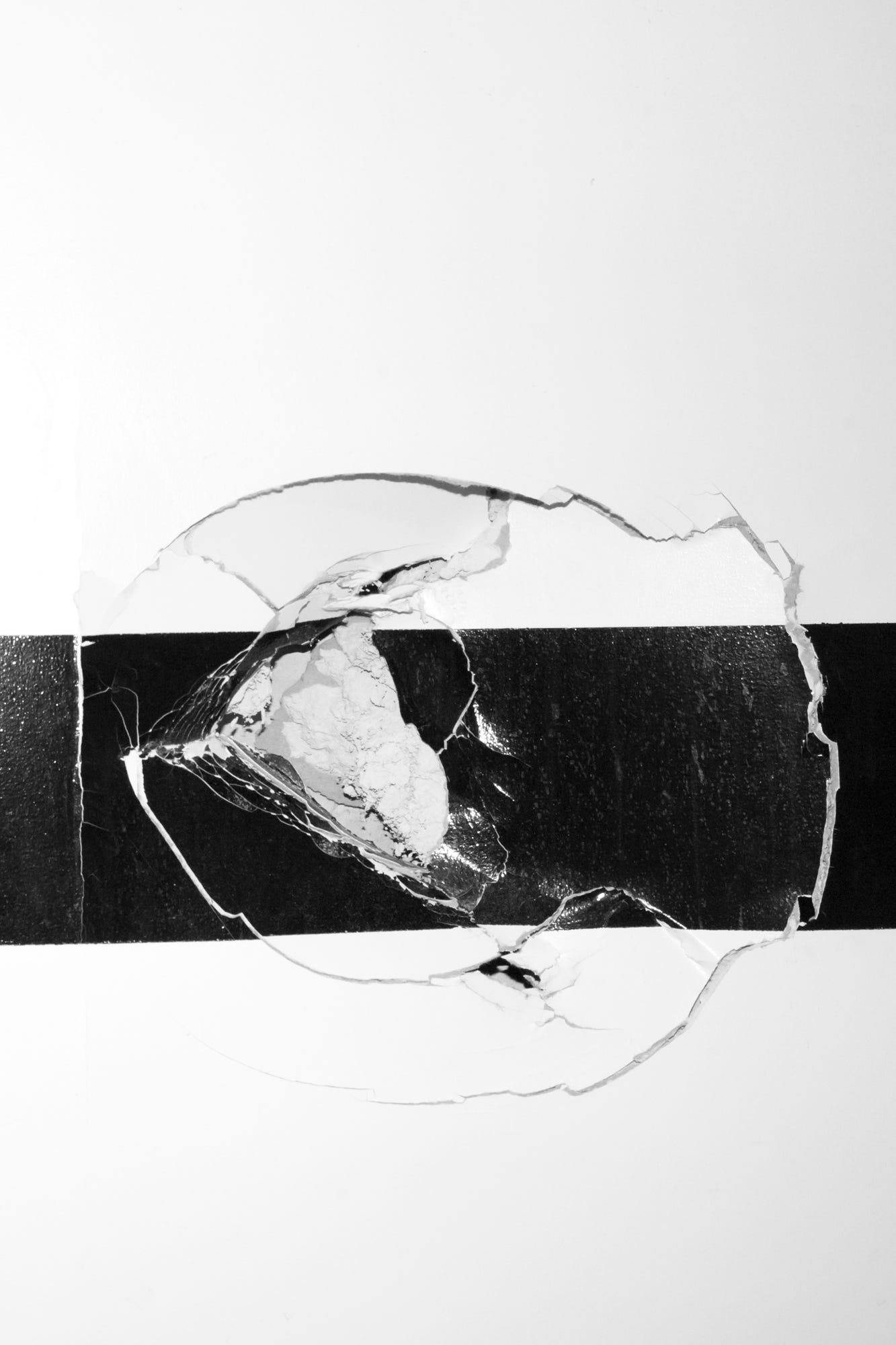

One day, while photographing two jiu jitsu fighters, Paco and Italo, I noticed a hole in a wall behind them. I asked how it got there, and they told me that their colleague had been killed after a tournament in Rio, randomly on the street, and that when their friend had heard the tragic news he had put a hole through the wall. With time I realized that the spaces that these men fight in are also filled with their own powerful energetic charge. In gyms in New York and New Jersey and at a National Guard training base in Peekskill, I’ve not only photographed men fighting, but also punching bags, holes punched through walls, exercise equipment, jiu jitsu dummies, boxing trophies, mirrors stained with blood and sweat and dirt, ripped posters, speaker towers, gym mats, boxing rings, dumbbells, locker rooms, head gear. Many of these things can take on sculptural qualities when they’re isolated and ‘quoted out of context’, and that interests me, too. With time I hope to develop this component of the work more, particularly the hole punches, which one day I hope to show as a grid of hole punch prints in an exhibition of the work.

What camera gear/editing setup did you use for Men Fighting & The Spaces They Fight In?

The work is made with a Leica M10 and a 50mm lens. Some were made with an on camera flash.

How did you achieve the look of your photographs in Men Fighting & The Spaces They Fight In and could you take us through the process?

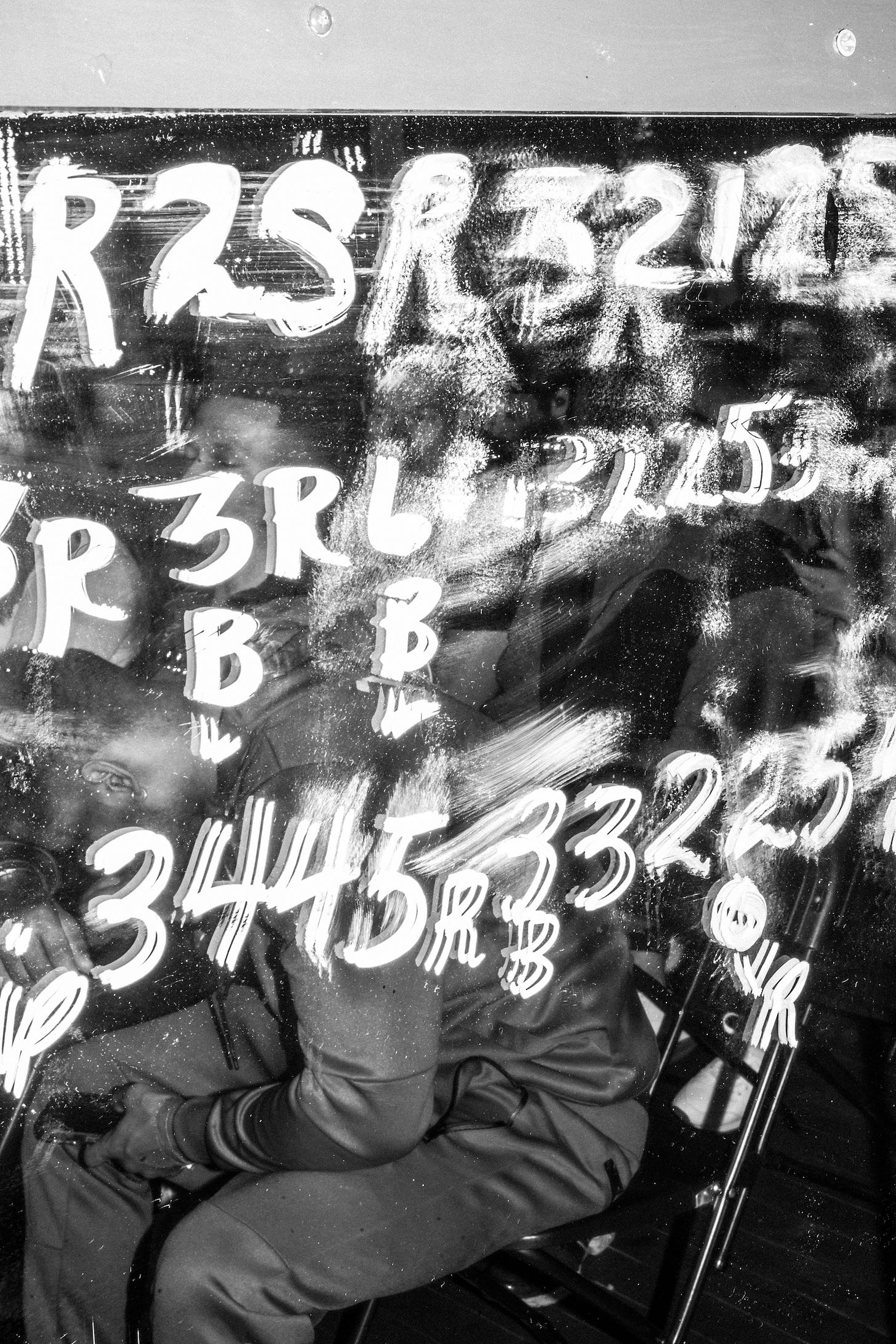

I work with a very high ISO, regardless of whether I use a flash or not, because it frees me up to have a high shutter speed and it adds a certain type of grain that is typically associated with a romantic, lyrical style of photography that I’m very drawn to. I want to make images that are visually rigorous and that seduce people. I’m interested in how black and white photography can function as a powerful short hand for thinking through questions about memory, mythology, and tradition. I’m also interested in beauty. It’s useful - not necessarily for its own sake, although that can be a wonderful, life-affirming thing too, but beauty can be employed to encourage people to look deeply as an entry point for thinking something through. Ambiguity is useful for exactly the same reason. Generally, I don’t make work to share answers or to insist on polemics. I make work as a way of asking questions and sharing that process with my community. With this work that has manifested as working with close-up, tight, graphic compositions as a way of channeling the feeling of a fight into the frame of a photograph.

Where do you see photography versus AI? As competition or do you embrace it in your workflows?

I don’t see it as competition. I see it as a way of understanding how we make images as a collective, and as an interesting way of thinking through conceptions of sentience and the parameters of authorship. In my work with Andrea Orejarena, who I often work with as an artist duo, we have generated some AI images for our work ‘American Glitch’ which will be included as one aspect of our work in our forthcoming book published by Gnomic Book in December.

Also, for me photography is about going out into the world. It’s about an exchange. That process remains unchanged, even if my work begins to integrate AI in some ways. It’s an exciting new technology that can be used as a powerful tool.

The advent of AI image technologies has had a strange effect on how I photograph, how I see my own work, and how I see the work of other artists.

Since seeing some of the strange body contortions and uncanny arrangements created through glitches in AI images I have started to be aware of how these forms appear in the world in front of me. There’s something cyclical in all of this - AI images are composites of billions of data points and images extracted from the real world, I view them, then I look for confirmation of their existence when I go offline and out into the world again.

I wonder - if I told you that certain photographs in ‘Men Fighting & The Spaces They Fight In’ were made by AI - would you believe it? Even though I made them and did not use AI, in some cases I think I might still believe that AI could have made them.

The other day I looked at my favorite photograph by Evelyn Hofer - ‘Springtime. Washington. 1965’. The photograph shows a policeman on a motorbike in front of a cherry tree in brilliant color. It has always struck me because of the way Hofer juxtaposes this stern, possibly violent police man with the soft, peaceful, natural surroundings. Even though the photograph was made several decades ago, and even though I know this image well and have been thinking about it for years, when I saw it recently I couldn’t help but think that Mid Journey had made it.

Where do you see photography versus AI in 10 years from now?

I think it will get rid of some of the drudge work and that the best artists will find ways of incorporating it into their practice with intelligence, humor, and curiosity. Duchamp said something about going beyond the labyrinth beyond time and space into a clearing…I think the art I love is a world building exercise that reflects its maker’s relationship to the world and to themselves and that these technologies can aid that, just like Camera Lucida and Camera Obscura did with painters. AI will also, of course, change everything in ways I do not have the capacity or the knowledge to predict, some of them probably not all good. Just as the invention and commercialization of photography changed so much starting in the mid 19th century - from the jobs of working portrait painters being replaced by portrait photographers, to how events were reported and how information was disseminated, to systems of knowledge and imperialist power being bolstered through the manipulative use of photograph - so too will AI change who has what type of work, how we consume information, and who has power.

It certainly won’t be making comical glitches with the pope’s hands for much longer. It will make us question what is real and what is constructed with a heightened intensity. It may also imagine utopias we have not had the ability to create.

That’s it for this newsletter!

If you have any suggestions for interviews, features, topics, interesting work or photo books that I should check out, don’t hesitate to leave a comment or reach out!

Stay safe and keep shooting.

Kim

Follow Nowhere Diary on Instagram and recommend it to a friend or a colleague!