Books (A guide to the photo books you should own) Part 2 of 2

Photo books you should add to your collection — fall 2022

This is the second installment of my guide to my favorite photo books that should be added to your collection or your wishlist.

Dieter De Lathauwer: It Didn’t Take Me Long to Realize the Escape, Once Again, Wouldn't Work — Void (2022)

This work is simple in its elaboration: made in one afternoon on an island with a turbulent history. It follows a clear and linear course in which the misty afternoon slowly slips into the darkness.

'It didn’t take me long to realize the escape once again wouldn’t work' by Dieter De Lathauwer became a reflection on place and walking as a solution for inner problems. It was a failed attempt to escape. Started as a known approach to the landscape. Ended with the landscape turning out to be an obstacle. This intimate and poetic book is about accepting failure and weakness, and turning it into something new.

Baldwin Lee: Baldwin Lee — Hunters Point Press (2022)

In 1983, Baldwin Lee (b. 1951) left his home in Knoxville, Tennessee, with his 4 × 5 view camera and set out on the first of a series of road trips to photograph the American South. The subject of his pictures were Black Americans: at home, at work, and at play, in the street, and among nature. This project would consume Lee—a first-generation Chinese American—for the remainder of that decade, and it would forever transform his perception of his country, its people, and himself. The resulting archive from this seven-year period contains nearly ten thousand black-and-white negatives. This monograph, *Baldwin Lee*, presents a selection of eighty-eight images edited by the photographer Barney Kulok, accompanied by an interview with Lee by the curator Jessica Bell Brown and an essay by the writer Casey Gerald. Arriving almost four decades after Lee began his journey, this publication reveals the artist’s unique commitment to picturing life in America and, in turn, one of the most piercing and poignant bodies of work of its time.

Abigail Varney: Rough & Cut — Trespasser Books (2022)

Rough & Cut documents Abigail Varney’s journeys to a place in central Australia called Coober Pedy. The town owes its existence to the discovery of opal seams in 1915, an iridescent gemstone that formed from water that once covered the desert landscape. This precious opal has been mined through a series of booms and busts, almost into oblivion. Beyond the mullock heaps and away from the sun's searing heat lies underground dugouts inhabited by Coober Pedy’s remaining miners, still dreaming of one last opal-rich strike. Keeping the idiosyncrasies of the town's personality alive and well, Varney’s encounters are an insight into the characters that call this place a forever home. Captured are the remnants of this magnetic, surreal landscape shaped by its extremities.

Roger Richardson: Let Me Sow Love — Deadbeat Club (2022)

When politicians and pundits talk about the heartland, or the heart of the country, they’re generally not pandering to places like Roger Richardson’s Middletown, which is located in Orange County, in New York’s Hudson Valley. Yet the people and places in Let Me Sow Love exist right smack in the middle of myriad 21st-century American realities. Refreshingly, though, there’s not so much as a whiff of polemic in Richardson’s photographs. As the title suggests, this is a book full of what feel like genuine and compassionate interactions and engagements, as opposed to the now-expected confrontations. You sense right away that Richardson knows this place intimately, and these are his people. As a result, Let Me Sow Love presents with remarkable clarity a compelling portrait of an utterly realistic human community at a unique and radically insecure moment in the country’s history.

The late Philip Levine, arguably the greatest working-class poet of the late 20th century, once said that his goal was to write poems so transparent that “no words are noticed. You look through them into a vision of the people, the place.” Time and again, Richardson realizes Levine’s vision through his photographs, and it’s a vision that will be achingly familiar to anyone who grew up in or has spent time in strikingly similar working-class cities and towns all over the United States.

Sem Langendijk: Haven — The Eriskay Connection (2022)

To whom does the city belong?

Haven tells the coming of age story of a boy in a rapidly changing environment, based on memories of surroundings that no longer exist. Sem Langendijk (NL) witnessed the unrooting effects of gentrification during his upbringing in the periphery of a large city. After the neighbourhood transformed into a waterfront, Langendijk realised he no longer identified with this area. He lost his connection to the place he lived in for nearly thirty years.

This body of work is the result of a long-term research project into shifting demographics, waterfront development and the dynamics of gentrification. Due to social inequality and urbanisation, people are continuously driven to relocate, particularly within post-industrial cities.

Haven brings together the environments of different port cities in a documentary fiction, highlighting the transformation of disused docklands and the communities that reside there. A second chapter contains the background research, providing context for the personal testimony that makes up the first part.

Eli Durst: The Four Pillars — Loose Joints Publishing (2022)

The Four Pillars grew out of a relationship with a faith-based self-help group that Durst photographed over several years. Despite their ostensibly comfortable lives, these affluent suburbanites felt unfulfilled and directionless. They met weekly in church basements to discuss spiritual and secular strategies to find meaning and purpose, and to deconstruct the markers of success, progress and identity within middle-class American society.

Durst's staged, inventive images build organically on this self-critical base structure by inventing scenarios that interrogate the relationship between the individual and the group, the norms we aspire to, and the social gravity that holds these two in alignment. Durst takes the details of these scenarios – mundane family portraits, team bonding exercises, pregnancy groups, school gyms, amateur theatre, county fairs – and amplifies their strangeness, through a lens that is at once factual, fictional, banal and absurd.

Wouter Van de Voorde: Death Is Not Here — Void (2022)

“In July 2021, together with my son, I dug a hole in my backyard. During this excavation, I unearthed the grave of one of my old chickens, who had died a few years earlier. Coinciding with this event, I was about to become a father for the second time, we were in a Covid-19 lockdown, and I was making little still-lives with fossils I had collected years back. A peculiar convergence of death/life and permanence/impermanence occurred during the period I made these images. Death is Not Here is a personal time capsule capturing and preserving this time in my life.” —Wouter Van de Voorde

Diogo Simões: A Zona — Pierre von Kleist Editions (2022)

A Zona is Diogo Simões´ first book. Twelve years in the making, it marks the arrival of a major force in Portuguese photography. All the photos were done in Margem Sul, Tagus river south bank, opposite Lisbon. A humanistic, poetic, politically engaged hallucinatory record of a territory with a strong industrial and postcolonial past. A beautiful land with mountains, white sanded beaches, dolphins and ghettos.

Simões is a son of the land. This is his territory. A Zona makes justice to Margem Sul, in all its Prehistoric, Roman, Muslim glory. Indeed, a Holy Land.

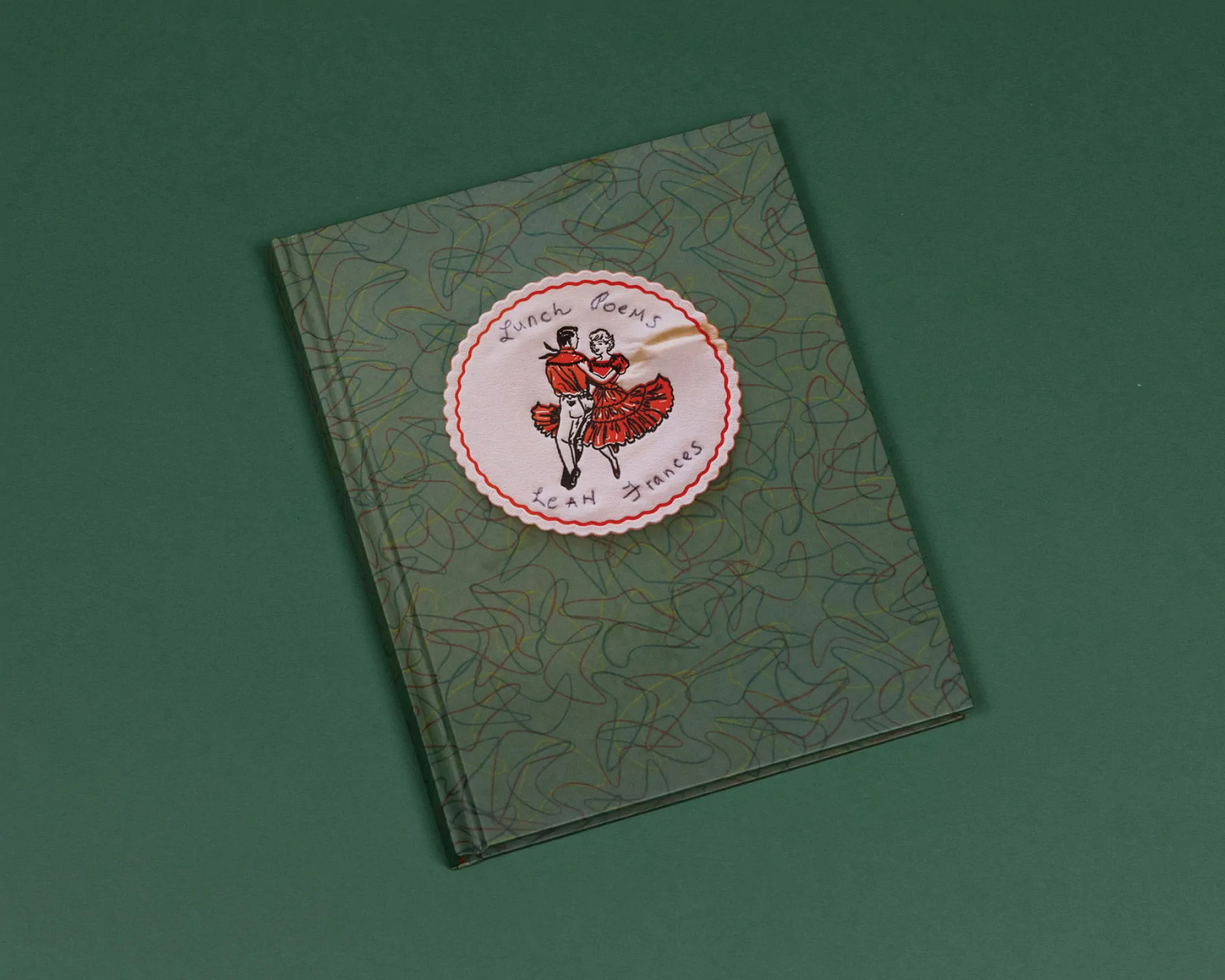

Leah Frances: Lunch Poems — Aliens in Residence (2022)

The photographs in Lunch Poems highlight “third spaces”: communal settings outside of home and work, such as taverns, church picnics, diners, restaurants, and movie theaters. Actively using photography to explore the residue of time and human effort, Leah creates portraits of place, mindful of the individuals who have been there before and may be there again. Imaginary one-to-one conversations with these ghosts, so to speak, allows her to invest in the possibility that within this divided nation, we might, one day, understand and respect each other. Harnessing light to grasp at moments of joy in complicated environments, with these images, she hopes to forge an opening for deep looking and the exploration of multiple layers of meaning, an encounter with complex histories rather than one-dimensional, familiar tropes.

That’s it for this newsletter!

If you have any suggestions for interviews, features, topics, interesting work or books that I should check out, don’t hesitate to reach out!

Keep shooting and stay safe.

Kim

Find Nowhere Diary on Instagram and Twitter